This article could be titled “what is FTP?”, but that sounds too SEO-optimised.

After doomscrolling through an /r/velo thread over the weekend and discussing the extent of confusion and conflicting information from the safety of a private (and more supportive, curious, and generous) community, I ended up trying to offer my own interpretation of, first, why is there so much confusion around the definition of Functional Threshold Power (FTP)? And how do I interpret the hinge term in that definition: “quasi-steady state“.

I don’t want to put words in anyone’s mouth here, so this is really just my own current perspective on the understandable confusion people seem to have with the definition(s) of FTP, and how I interpret it myself, with my current best understanding of contemporary exercise physiology.

How is FTP Defined by it’s Originator?

Dr. Andrew Coggan defined FTP originally, so I’m told, on the Wattage list in early 2003 (maybe before, I don’t know, I wasn’t there. But I have it on authority from people who were).

[P]robably the easiest and most direct way of estimating a rider’s functional threshold power is therefore to simply measure their average power during a ~40 km (50-70 min) TT.

When I started getting into bike training in the mid-2010s, FTP was a well established term from Coggan & Hunter Allan’s famous Training and Racing with a Power Meter.

FTP is the highest power that a rider can maintain in a quasi–steady state for approximately one hour without fatiguing.

So there it is. That’s the definition. Simple.

But the first source of confusion arises immediately when the reader tries to reconcile the qualitative definition given in the first portion “the highest power that a rider can maintain in a quasi-steady state without fatiguing…” with the quantitative approximation given in the next breath “… for approximately one hour.”

(A few pages later in TaRwaPM FTP is defined more literally: “FTP is defined as the highest average wattage or power that you can maintain for 60 minutes.” But this appears to be an offhand remark forgetting the proper nuance of the definition. So we’ll ignore it.)

Dr. Coggan has remained commendably consistent in repeating this definition over the years, including in the aforementioned /r/velo thread (allegedly… he kinda pretends to be anonymous, but people seem to know it’s him? I don’t quite get the vibe, honestly).

Construct versus Operational Definitions

The first part of this sentence is a construct definition. “quasi-steady state” is a concept or a construct of a quality that cannot be literally measured directly. What is “steady” in a “quasi-steady state” ? Unclear (I’ll get there).

Power output can be measured directly in watts. Intensity cannot be measured directly, and represents a qualitative phenomenon. We have to operationalise a method to estimate or approximate intensity if we want to quantify it.

We could measure V̇O2, lactate, heart rate, RPE, or some other quantitative metric which we can hopefully justify as a valid proxy for intensity. But we cannot measure the quality of intensity directly. Just like we cannot measure a “quasi-steady state” directly.

So the second part of the sentence “… for approximately one hour.” is an irresistible operational definition for how we might estimate FTP, but is not the literal definition of FTP. But it’s no wonder that people latch on to the firm ground of the 60-minute number after wading through the murky bog of “a quasi-steady state”.

I am told (and I believe I have heard Dr. Coggan himself say on a podcast) that the most common method to test FTP – the 5+20-min time-trial average power *0.95, pseudonymous “FTP test” was developed by Hunter Allan, and Dr. Coggan was not the biggest fan of this, preferring the 60-min TT as a better proxy.

Elsewhere on the Wattage forum, he proposed (and/or cautioned against?) other methods for estimating FTP, but were not in themselves literally FTP. The “seven deadly sins”. The 5+20min*0.95 protocol was not on this list.

Likewise, Dr. Coggan has professed not to be a fan of ramp-test estimates of FTP. A stance I strongly agree with.

What is the Maximal Metabolic Steady State?

To my current best understanding, a “quasi-steady state” is conceptually similar enough to the concept of the maximal metabolic steady state (MMSS). This is our current in-favour construct term in sport science and exercise physiology, for the real true un-measurable transitionary state between “steady” and “non-steady” metabolic responses. i.e., a “quasi-steady state”.

The most accepted definition for MMSS is something like this paragraph below, from a keystone 2016 paper on Critical Power (I’m aware I am using a definition provided for one term, to define an entirely different term, but bear with me🙄).

We can see, the authors begin by talking about CP conceptually, then continue to discuss the operational limitations for the actual methods used to test CP. So the operational definition of CP is the test which can be used to estimate the state which CP is trying to estimate, which would go on to be termed the maximal metabolic steady state, if that makes sense?…

CP represents a metabolic rate. In contrast to historical definitions, CP is now considered to represent the greatest metabolic rate that results in wholly oxidative energy provision, where wholly oxidative considers the active organism in toto and means that energy supply through substrate-level phosphorylation reaches a steady state, and that there is no progressive accumulation of blood lactate or breakdown of intramuscular phosphocreatine (PCr), i.e., the rate of lactate production in active muscle is matched by its rate of clearance in muscle and other tissues. It is important to note here, however, that there will always be some error in the estimation of CP, and CP varies slightly from day to day in the same subject (91). Although it is possible to estimate CP to the nearest watt (e.g., 200 W), given a typical error of ~5%, the ‘‘actual’’ CP might lie between approximately 190 and 210 W in a given individual. Therefore, asking a subject to exercise exactly at his or her estimated CP runs the risk that he or she will be above their individual CP with associated implications for physiological responses and exercise tolerance. As CP is primarily a rate of oxidative metabolism (rather than the mechanical power output, by which it is typically measured), it might be more properly termed ‘‘critical V ˙ O 2 .’’ During cycling, the external power output corresponding to this critical V ˙ O 2 can be altered as a consequence of the chosen pedal rate for example (6).

Their use of “critical V̇O2” near the end of the paragraph gets nearer to the mark of what would subsequently become known as MMSS. However, “critical V̇O2” is still an operational term, since V̇O2 can be measured, while metabolism cannot be measured, and is therefore a true construct term.

At least, this is how I currently think about it.

So MMSS could be defined as “the greatest metabolic rate that results in wholly oxidative energy provision”. In our previous meta-analysis which hinged on a question of defining training above or below MMSS, we defined it as such:

(free full PDF available here https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374091331)

MMSS is considered to be the exercise intensity that coincides with the maximal sustainable oxidative metabolic rate. MMSS is a theoretical threshold that separates the heavy and severe intensity domains (Fig. 1), where exercise performed within the heavy domain allows for the attainment of a quasi-steady state systemic oxygen consumption ( ̇V O 2 ) . A metabolic steady state is not attainable in the severe domain

The reference to “quasi-steady state” was an intentional homage to the definition of FTP.

What is a Quasi-Steady State?

To eventually cut to the chase, what does “quasi” mean here? Well you can google the word itself, but to my interpretation, in this context it means that maximal task tolerance (a better way to describe task failure) will occur without the global whole-body metabolic rate (V̇O2) approaching V̇O2max. And without the peripheral local muscle metabolic milieu (PCr, Pi, H+, pH, other ionic gradients, etc.) reaching critical concentrations (accumulation and/or depletion) which disrupt muscle contractile force production (our working definition for fatigue).

These are the measurable metabolic components which we usually think of as contributing to fatigue and attainment of maximal task tolerance. But de facto, if maximal task tolerance occurs with these global & local disruptions at an elevated but not critical (maximal) rate, then something isn’t in homeostasis. Hence “quasi-steady state”.

It’s like things fall apart not because any one component process has reached it’s maximal rate- or capacity-limitation, but because everything is just a little bit disrupted and the whole flux through the system becomes unsustainable. I’m being reeeal handwavy here.

What Causes Fatigue in a Quasi-Steady State?

Now let’s get un-handwavy.

I’ll refer to an excellent experiment and discussion on the metabolic responses and fatigue mechanisms associated with maximal task tolerance in the three primary intensity domains we use in ExPhys:

- Moderate intensity domain: low-intensity below the first metabolic breakpoint (e.g. lactate/ventilatory threshold 1; gas exchange threshold (GET)), analogous to zone 1 in a 3-zone physiological model, or zones 1-2 in a 5+ training zone model.

- Heavy intensity domain: intermediate intensity between the first and the second metabolic breakpoints (between LT/VT1 and 2; or GET and RCP; below FTP, CP, MMSS, MLSS, etc.), analogous to zone 2 in a 3-zone model, or zones 3-4 (sometimes 5) in a 5+ zone model.

- Severe intensity domain: high-intensity above the second metabolic breakpoint (LT/VT2, FTP, CP, MLSS, respiratory compensation point (RCP), etc.), analogous to zone 3 in a 3-zone model, or zones 5+ in a 5+ zone model.

- (there’s a 4th extreme intensity domain, but we’ll ignore that for now)

The excellent paper from Dr. Matthew Black et al observes differences in fatigue mechanisms by having their subjects exercise to the maximal limits of tolerance at workloads within the three domains (up to 6 hrs continuously for one participant in the moderate domain!😮).

This study is consistent with the notion that GET and CP demarcate exercise intensity domains within which fatigue is mediated by distinct mechanisms. Exercise intolerance within the severe-intensity domain (>CP) was associated with the attainment of a consistent critical muscle metabolic milieu (i.e., low [PCr] and pH). In contrast, moderate-intensity exercise (<GET) was associated with more significant depletion of muscle [glycogen]. The causes of fatigue during heavy-intensity exercise (>GET, <CP) were more obscure with intermediate changes in muscle metabolic perturbation and glycogen depletion being apparent. These results are consistent with the notion that both GET and CP demarcate exercise intensity domains characterized by distinct respiratory and metabolic profiles. Strikingly, CP represents a boundary above which both metabolic and neuromuscular responses conform to a consistent ceiling or nadir irrespective of work rate and exercise duration.

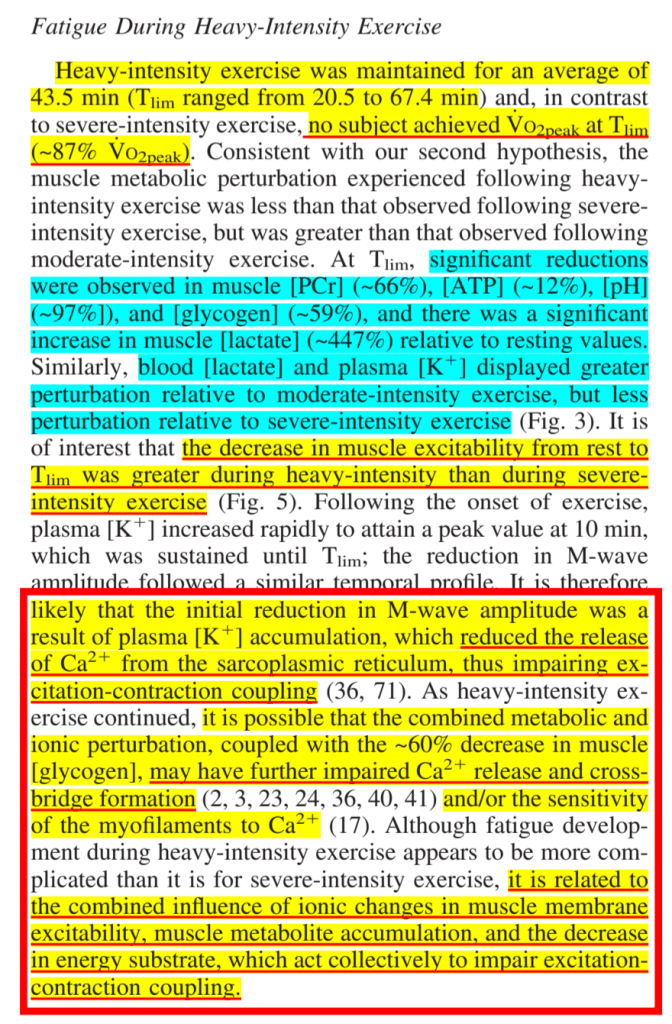

To further copy paste their discussion of fatigue mechanisms in the heavy intensity domain of most interest:

Heavy-intensity exercise was maintained for an average of 43.5 min (T lim ranged from 20.5 to 67.4 min) and, in contrast to severe-intensity exercise, no subject achieved V ˙ O 2peak at T lim (~87% V ˙ O 2peak ). Consistent with our second hypothesis, the muscle metabolic perturbation experienced following heavy intensity exercise was less than that observed following severe intensity exercise, but was greater than that observed following moderate-intensity exercise. At T lim , significant reductions were observed in muscle [PCr], [ATP], [pH], and [glycogen], and there was a significant increase in muscle [lactate] relative to resting values. Similarly, blood [lactate] and plasma [K ] displayed greater perturbation relative to moderate-intensity exercise, but less perturbation relative to severe-intensity exercise (Fig. 3). It is of interest that the decrease in muscle excitability from rest to T lim was greater during heavy-intensity than during severe intensity exercise (Fig. 5). Following the onset of exercise, plasma [K ] increased rapidly to attain a peak value at 10 min, which was sustained until T lim ; the reduction in M-wave amplitude followed a similar temporal profile. It is therefore likely that the initial reduction in M-wave amplitude was a result of plasma [K ] accumulation, which reduced the release of Ca 2 from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, thus impairing excitation-contraction coupling (36, 71). As heavy-intensity exercise continued, it is possible that the combined metabolic and ionic perturbation, coupled with the ~60% decrease in muscle [glycogen], may have further impaired Ca 2 release and crossbridge formation and/or the sensitivity of the myofilaments to Ca 2. Although fatigue development during heavy-intensity exercise appears to be more complicated than it is for severe-intensity exercise, it is related to the combined influence of ionic changes in muscle membrane excitability, muscle metabolite accumulation, and the decrease in energy substrate, which act collectively to impair excitation contraction coupling.

So Dr. Coggan might not agree with me (probably won’t), but that edge-of-when-things-are-just-about-barely-not-quite-falling-apart seems reasonably synonymous with “quasi-steady state” to me.

What Would Maximal Task Tolerance Look Like at a Quasi-Steady State?

If we are working on the edge of FTP (the real true unmeasurable state of quasi-steady state FTP-ness) we will eventually reach task tolerance, in one of two different ways:

(1) If our in toto whole body metabolic rate continues to increase at a constant external workload, our V̇O2, [lactate], ventilation, internal core/muscle/brain temperatures, etc. continue to drift, and our locomotor muscle metabolite concentrations continue to accumulate/deplete, then we are definitionally not in a steady-state, and our metabolic rate has exceeded our MMSS as it truly, conceptually exists at that moment, on that day, under those acute conditions.

Even if the external workload has remained below our best-estimate of FTP/CP/etc, our internal metabolic rate has exceeded MMSS/quasi-steady state FTP-ness. And we will reach maximal task tolerance relatively sooner, likely much sooner than the 60 minute gold-standard estimate for FTP.

(2) If our unmeasurable metabolic rate, and those measurable metabolic responses do not continue to drift, and they maintain at an elevated quasi-steady state, then we will reach maximal task tolerance more slowly. And our metabolic rate is definitionally below MMSS, even if our external workload exceeds our best-estimate of FTP/CP/etc. (usually doesn't work like that, unfortunately).

We will still reach maximal task tolerance, but probably slower, maybe around 60 minutes, maybe shorter, maybe longer.

Side note: there is a distribution for individuals’ ability to maintain FTP to maximal task tolerance (or TTE). The mean/median of that distribution does not necessarily at 60 min, but 60 minutes is at least contained within the 95% prediction interval (but not necessarily the confidence interval) of that distribution. Different subgroups by training status, fitness, age, etc. will have different distributions for FTP @ TTE. Some closer to 60 min, some further away. It’s a nice goal to train for, but you’re not a bad person if you can’t hold your FTP for 60 minutes.

For example, in this cohort of 120 competitive (amateur to World Tour) cyclists, the average difference was 5+20min TT *0.95 predicted-FTP was 12 W lower than their actual 60-min TT power, with a distribution of individuals between 80 W lower, to 56 W higher.

Maybe an interesting follow-up question is, if we are at a quasi-steady state metabolic rate which allows us to go longer, are we more or less likely to begin drifting toward non-steady state V̇O2max the longer we go?🤔

What happens if we first exceed MMSS/quasi-steady state, then reduce our external workload below that threshold? Is the power associated with MMSS/FTP still the same power associated with MMSS/FTP on the way down, as it was on the way up? (a concept known as hysteresis).🤷♂

So What?

When we are working firmly in the Severe intensity domain above FTP/CP/MMSS/etc. then we should experience the former situation of non-steady state fatigue.

When we are working firmly in the Heavy intensity domain below FTP/CP/MMSS/etc. then we should experience the latter situation of quasi-steady state fatigue.

The closer we get to FTP/CP from below, on any given day, in any particular acute conditions, the more likely we are to experience the former situation of quasi-steady state fatigue.

The closer we get to our operational power estimate for the construct of FTP/MMSS, the more uncertainty, or the less confidence we have that we will remain in a quasi-steady state and experience that latter situation of fatigue, if that is our intention for the session.

So in my opinion, if we want to be working submaximally below FTP/CP/MMSS, and we want to experience quasi-steady state fatigue for our intended training stimulus for that session, we should aim for a workload in the middle of the zone, not at the absolute upper boundary.

We train in zones, not at thresholds! Zones are big, play around in them!

(in the tweet below, I’m talking about the meme zone 2 at lower intensity, but the same message holds for tempo/sweet-spot/other training sessions distinctly intended to be below FTP/CP/MMSS/etc.)

Is the Definition for FTP Uniquely Confusing?

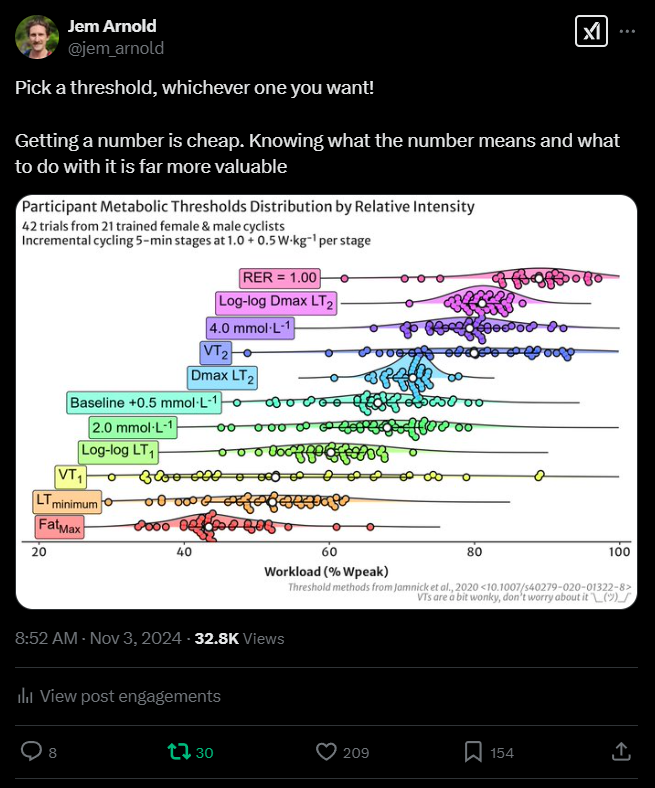

Oh god, no 😂 I mean, look at all the competing definitions for “lactate threshold” we have:

Or just different thresholds in general, that I visualised from some of our own study data:

The reality is that language and definitions drift over time and between different groups of humans. Because humans communicate to seek common understanding with each other, and our understanding develops locally, communally, socially.

Different humans understand and ‘click’ with different language, and so different understandings of language develops to communicate diverse ideas among diverse groups of humans. It’s fine. This is why we have language, to communicate ambiguous and complex ideas. Unfortunately, the internet seems to discourage nuance and such scary social humanist behaviour as empathetic communication.

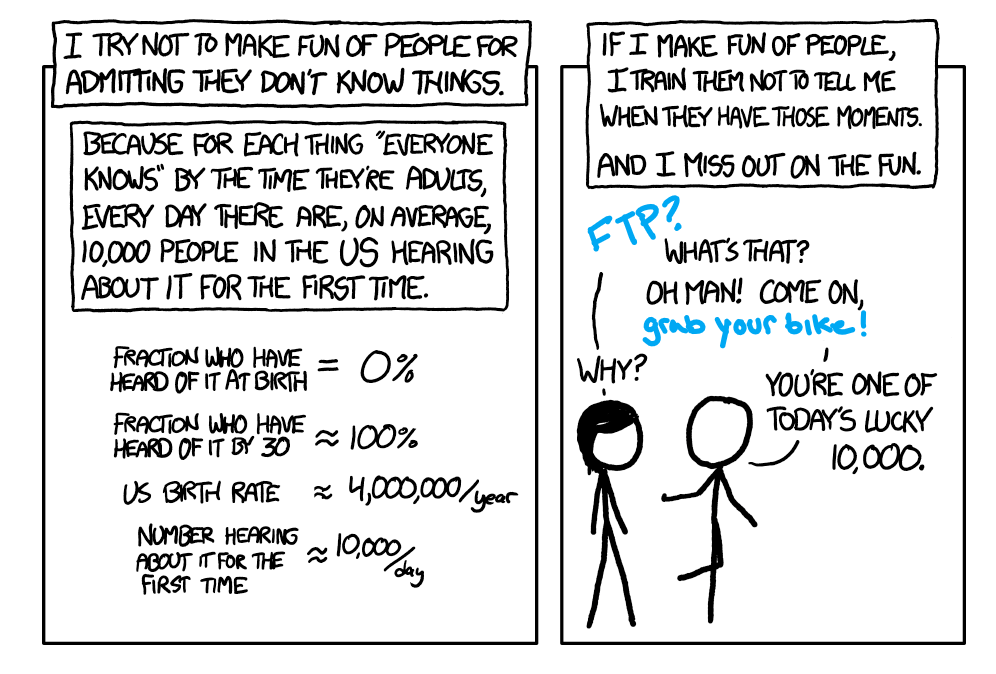

And there is always another human encountering a non-intuitive idea for the first time. We can roll our eyes and belittle them for not understanding something that we take for granted, or we can take pleasure in introducing them to a new idea and sharing our understanding of the world. (or we can just not get involved at all, that’s fine too.)

Great piece. Thanks for taking the time to put this together.

In my experience (I joined the Wattage List in 2004 and have saved messages going back to 2008), one of the things that people keep forgetting about re: FTP, is that the “F” stands for “functional”. Not sure applicable it is to compare to lab measures of various thresholds.

LikeLike

Thanks! I’m jealous, it would have been fascinating to be part of that community at the time. A golden era of training science and coaching, perhaps?

Yeah absolutely well said. The point of FTP was/is that it was a “functional” measure of endurance performance. Not a physiological measure. That’s actually part of the confusion I could have also talked about: FTP is defined as the power output associated with “quasi-steady state”. A hard quantitative external measurement associated with a vague internal transitional physiological state. That relationship has uncertainty baked in. It’s a moving target. And it depends entirely on the operational method used to obtain the observable part of that relationship, which is power output.

The intent behind FTP is great as a function measure of endurance performance. But like all other threshold estimates, it’s entirely dependent on the protocol used to estimate it. Every protocol has trade-offs. Some are better than others for certain contexts. It’s contingent on the athlete or the coach or the “end user” to understand the applications and limitations of the measurements they use.

But that’s a whole other conversation we could have, on the shift in “cost” from collecting quantitative data, to now filtering noise from our excessive volumes of data and distilling the relevant information, then the experience & wisdom to apply that information to real-world athletes.

Thanks for the comment!

Jem

LikeLike

Just saw this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61zuiF3-hDY

AC speaks (briefly) about quasi steady state

LikeLike

Thanks. Yup that’s a great conversation and brings the concepts behind “FTP” right back to their basics.

LikeLike